Satchel Paige by Sturm and Tommaso

Satchel Paige: Striking Out Jim Crow by James Sturm (writer) and Rich Tommaso (art). Jump at the Sun/Hyperion, 2008. 90 p., $9.99.

This week’s baseball comic is another work from James Sturm, this time in conjunction with Rich Tommaso. I’m assuming Sturm is writing and making the breakdowns, while Rich is providing the drawings/compositions. Though neither are credited with any particularly duty, the drawing is clearly not Sturm’s, but the breakdown of the story into panels is reminiscent of his other works.

I’m never quite sure how to critique a children’s books. I’m not the intended audience, and I don’t have a lot of background with similar books (I read when I was a kid but not a ton of children’s books and not so as I remember them). This book is, like it’s predecessor in this series Houdini: The Handcuff King, written for children, and not as relevant, in my opinion, to the adult reader. Either way, I’ll do my best, though I can say, right off, that I’m not overly impressed.

I have to start by noting how deceptively titled and marketed this book is. To consider this a book about Satchel Paige is an over statement. To say that this book “follows Paige from his earliest days on the mound though the pinnacle of his career” and that the “author and artist share the story of a sports hero who defied the barriers of race to play the game on his own terms,” as the back of this books does is misrepresentation. This is not a biography of Satchel Paige, who is widely considered one of the best pitchers ever in baseball, nor is it a book about his defying of race barriers.

The bulk of the story belongs to and is narrated by a black man from the south name Emmet (a name which one only infers because his son is “Emmet Jr.”). In 1929 he heads off from Alabama and his life as a sharecropper to play in the Negro Leagues, with one of the all black baseball teams, and tries to earn enough money to support his family and buy a home that isn’t a shack. The main focus of the first part of the book is a baseball game that Emmet’s team plays against Satchel Paige’s team. Emmet manages to score a run off the young superstar but ends up permanently damaging his knee during his slide into home.

The second part of the book takes place over a number of years from 1930 through 1943, as we learn a bit more about Emmet’s life after his injury. He gives up baseball, doesn’t talk about it, and becomes a farmer, trying to support his wife and child in a place that is still controlled by wealthy white men. We see his struggles as the twin white sons of the old landowner exert their power over him and physically intimidate him and his son to keep Emmet, Jr. out of school and working in the fields. During this section we see, less a baseball game than a baseball exhibit, where the twin sons, on their way to join a minor league ball club, hit home runs. This section will provide some historical insight for the younger reader, who might (probably) be unfamiliar with certain aspects of post-slavery repression of blacks in the US: lynching, segregation, and general intimidation through wealth and power.

The third part of the book features a 1944 baseball game between Satchel Paige’s All-Stars and the local white all-stars in Emmet’s town. This scene is explicitly singled out as an example of a black man standing up to and beating a white man(men). Paige strikes out both white twins and one other white player. This example is a kind of a life lesson for the protagonist’s son (“Another first for Emmet, Jr.: Seein’ a black man sass a white” (69)), and rouses Emmet himself from a long silence to his son about his baseball days. They go home and Emmet shares stories with his son. Emmet’s narration references remembering “the type of man” he is, and hoping that his son will remember “who he can be” (85). This is accompanied by Emmet giving his son the baseball which Paige gifted him back in 1929 when he hurt himself. This provides an “uplifting” ending, but I don’t feel that this sense of “who you can be” is really earned. The issues that provide the focus in the second part of the book are not addressed nor do we see any indication how Paige’s striking out a few white men really changes anything for Emmet or his son beyond them bonding over baseball. It’s a simple and simplistic moral to the story, one which is probably suited for an audience of children, but feels hollow to me. In comparison, Sturm’s The Golem’s Mighty Swing’s thematics of identity and spectacle appear much more sophisticated.

One of the most interesting formal aspects of this book–which, somehow, I only noticed after a few readings–is that there is not a single word balloon in use. For some this would actually disqualify Satchel Paige’s identity as a comic, but for me it shows an example of an interesting narrative tactic. The main story is narrated by Emmet in the present tense, though the narration itself shows a certain retrospective view on the events (not unlike the narration in The Golem’s Mighty Swing). Emmet reports all speech and provides commentary on actions. One unusual use of the reported speech comes late in the story where one of the white twins yells a racial slur at Paige during his at-bat. The narration of the man’s words are written in extra large letters, but still maintain their place at the top of the panel where one finds the narration throughout the book. The narration often doubles the images, as if either Sturm or Tommaso were not sure of the images’ ability to tell enough of the story (or maybe it’s a tactic to make the reading easier for a younger reader). Almost every panel contains narration, only the occasional action panel is left silent. The textual narration carries the greatest weight of the story, and it would be nice to see a little more reliance on the images. For the most part the visual narration is as much Emmet’s as the text. I don’t think we need to have his story completely scrolled out as text.

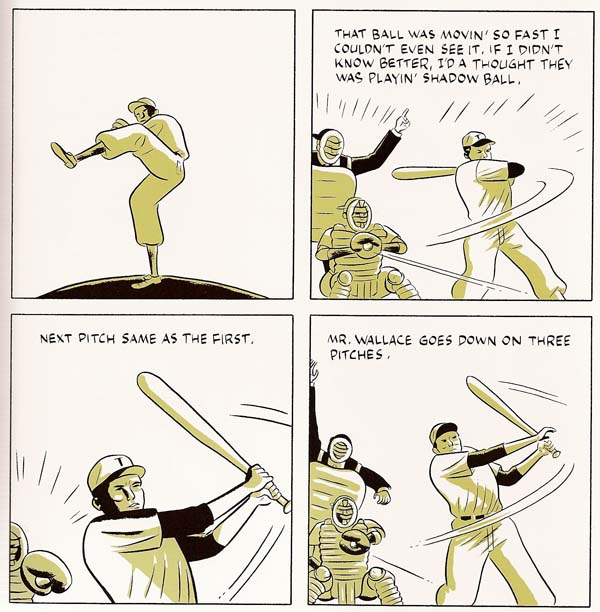

This sequence showing Paige striking out one of the twins, provides a good example that doesn’t need so much narration. The pitcher set-up and then the three repeated panels of a missed swing say just about all that needs to be said and is a great way to not only show the strike out but also show the speed with which it is accomplished: bang bang bang, you’re out. The umpire seen in panels 2 and 4 helps communicate the information and let us know that the image is not just a static sequence.

Two pages stand outside Emmet’s narration. Both show a montage of images in black and gray (as opposed to the rest of the art’s black and light olive) with typeset text that provide some extra narration about Paige’s activities. These two pages are the entirety of what might be considered biographical information on Paige. Otherwise he appears more as a mythical figure pitching in the two baseball games that bookend the story. These two pages are an odd fit for the rest of the book. They are clearly not coming from Emmet and mostly serve to give some credence to the idea that this book is about Paige.

Reading this volume back-to-back with Sturm’s solo baseball book, it’s hard not to make comparisons with not just the story but the art. Tomasso’s drawing is stiff and awkward in comparison with Sturm’s. The figures seem ill-suited to the action of the baseball games. His style is simpler and more abstracted than Sturm’s, though it has a certain charm that just feels poorly fit to this historical tale. This isn’t to say it’s all bad, there are some well-composed images, interesting figures, and use of lines and sound effects to convey the action of the game. The sequence below shows some of these conflicting aspects. The first panel is a well-done action panel with a dynamic sound effect, but the second and third are more problematic. The fielder in the second panel looks terribly awkward and the composition of the image focuses completely on that figure (he’s so centered). The third panel is just a bit confusing narratively, as the figure (I assume that is Emmet) seems to be running at top speed. Based on the background, he is running back to the plate from first. If the ball were called foul, why is he running like that with some much effort?

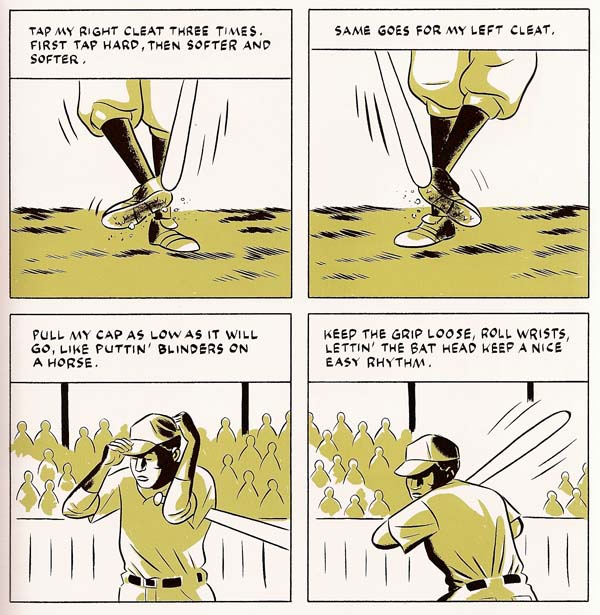

The baseball scenes themselves are not particularly exciting or different than what is seen in Golem. With the subject of Paige, there is a natural focus on the pitcher/batter conflict, which was missing in Cotton Woods. The panel pacing is well done, particularly in scenes where Paige himself uses time as a tool against the batters. We see Paige tying his shoe, walking around, joking with his fielders. In his at-bat, early in the book, against Paige, we similarly see Emmet try to take back some of the pacing of the game (see the sequence below). This is one of those moments you see a lot in a baseball game: the little batter’s rituals that are performed in endless variations. These panels also show a bit of the redundancy of the textual narration.

All in all, not a great comic nor a great baseball comic. I can’t speak for its effectiveness as a children’s book, though I wonder who this would appeal too. I’m not sure we get enough of a sense of Paige’s greatness to make him the mythic figure he needs to be for this book to really work for a younger audience.

Next week, I’m hoping to have a review of the baseball manga H2 by Mitsuru Adachi. Or at least a review of some part of it as the scanlation hasn’t quite reached all 34 volumes, and I don’t think I’ll even get the 28 that are scanlated read.

Previous Post in my baseball comics series: The Golem’s Mighty Swing by James Sturm

Next Post in my baseball comics series: H2