The Golem’s Mighty Swing

The Golem’s Mighty Swing by James Sturm. Drawn and Quarterly: 2001. 112p, $12.95.

Baseball month continues with this comic by James Sturm, the first of two baseball comics by Sturm I’ll be reviewing. Outside of his work with the Center for Cartoon Studies, Sturm is best known for historical fiction comics, included the recent collection James Sturm’s America (which includes this story). Even his Fantastic Four book Unstable Molecules is firmly situated in a historical context.

(While he shows a debt to Gotto, Sturm takes his own path, in this action panel, the sound effect is beautifully integrated with the ball. Significantly more effective than Gotto’s starbust images.)

The Golem’s Mighty Swing takes place sometime during the Prohibition era (1920-1933) in the American midwest. The main narrator is Noah Straus, the “Zion Lion”, a former major league ballplayer, who leads a barnstorming Jewish baseball team called the Stars of David. The team travels from town to town in a beat up bus, playing local ball clubs and taking abuse from the towns’ folks.

The story is divided into three parts. The first has the team playing a game in Michigan. They stick around town afterwards and a man name Paige approaches Noah about a moneymaking scheme where one of the players would dress up as the mythical golem during games. Noah is against the idea, but later, when the team’s bus breaks down, changes his mind. The second part covers the game and surrounding events when the team uses the golem idea. The golem seems to only heighten the crowd’s anti-semiticism and the game ends in a riot. The team only gets away thanks to a rain storm that washes out the game and disassembles the crowd. The third, and shortest part, is a bit of an epilogue, ten years later, where Noah goes to see another one of Paige’s schemes, a staged game where so-called big leaguers play again a bunch of men dressed as “hay seeds”.

A continuing theme in the book is the idea of spectacle and illusion. The Stars of David are all bearded jews, yet Hershl Bloom is actually Henry Bell, an african-american, and Mo Strauss (Noah’s younger brother) has a beard of shoe polish. The Golem is Henry Bloom in costume. Henry tells a story about a native american who played as an black man on a black ball club. The Stars of David offer themselves as a spectacle, which the crowds love to hate. In one scene a man calls into the bleachers at a women he knows. She doesn’t like baseball, but she’s there to “see the jews.”

The anti-semeticism of the crowds, in this context, seems to be as much about spectacle as any real hatred. A group of children throw stones at Mo and want to knock off his hat to see the horns underneath. They fall for the stories of jews as monsters. Paige plays up this idea with his Golem scheme. If the crowd thinks the jews are monsters, then he creates an even larger monster for them to see.

In the end so much of these spectacles come down to money. The Stars of David are trying to make a living, and Paige wants to make money off of them. The riot at the game with the Golem is even partly mitigated by the intervention of Mr. Putnam, the wealthy factory owner who set up the game. He wants to get his money worth from the game so he sends in the police to keep the crowd away from the team.

The story is mostly narrated by Noah. His words set the scene, act as a kind of announcer for the games, and allows for an easy compression of events which Sturm doesn’t feel the need to illustrate. Most of the story is also focused through Noah’s presence, but there are a few places where the focus travels to other characters and Noah’s narration drops out. At one point we follow Mo Strauss as he walks around town. People look at him suspiciously (though, in their defense, he stands in front of a farm house and watches a woman breast feeding), children chase him and throw rocks, and he ends up chasing one of the kids. The kid runs into a grocer’s sidewalk produce and knocks apples everywhere. Mo ends up talking baseball with the grocer and some other people. This is one of the only positive scenes of interaction we see between the Stars of David and other people. A small respite. In contrast, Noah’s narration drops out as Lev, one of the pitchers, heads into a town to a speakeasy for a drink and gets beat up. A third scene shows a newsboy hawking newspapers, while another, slightly crazy fellow runs around causing trouble and shouting about the golem. The townsfolk seem to look at this guy as a bit of a nut, yet, later, when the riot at the game occurs, he is there amongst the people and not all that different than the rest. They fall to his level as they fall for the spectacle.

This lack of narrative consistency went unnoticed my first time through the book. Once I noticed it, it threw the narration into question. Noah’s narration reads like he was telling a story to someone as if it were the present (i.e. “A fair had arrived yesterday,”). The more I think about it, the more odd and unstructured it is. Sturm complicates matters by occasionally using the narrative caption boxes for dialogue occurring in the story rather than Noah’s narration (which seems to exist outside the story). I don’t think it harms the story, but I wonder if there is something purposeful in it or if Sturm just didn’t consider it that fully. Noah’s narration exists mostly on a surface level, it doesn’t go into his feelings or psychology and I wonder how necessary it is for the first person element to be there at all. In general, I’d have liked to see a little more about the characters. Mo Strauss plays a fairly prominent role in a number of scenes, but the reader never gets a good idea at the whys of his actions, his anger. One even wonders why he plays baseball: for the love of the game? just to make money? to impress his brother? The use of the character hits at these questions, but does not explicitly raise or answer them.

(Sturm plays up the competition between pitcher and batter and the location of pitches.)

Enough about the narration, on to the baseball. In the acknowledgments section Sturm thanks, among others, Ray Gotto. Reading The Golem’s Mighty Swing so soon after Cotton Woods, I did notice Gotto’s influence in a number of the baseball scenes. A few of Gotto’s visual tropes make their appearance–the large foreground baseballs, expressive silhouettes, and the scoreboard as a narrative method–but Sturm shows the game in a much different way. In a 100 page comic book format, Sturm has a lot more space to work with than Gotto’s four panel dailies. We see the result of this in the way parts of the game slowly unfold. An early at-bat by Mo lasts more than 3 pages (25 plus panels). The tension between pitcher and batter is played up more than in Gotto’s work, as is more particulars of pitch number, location, and type.

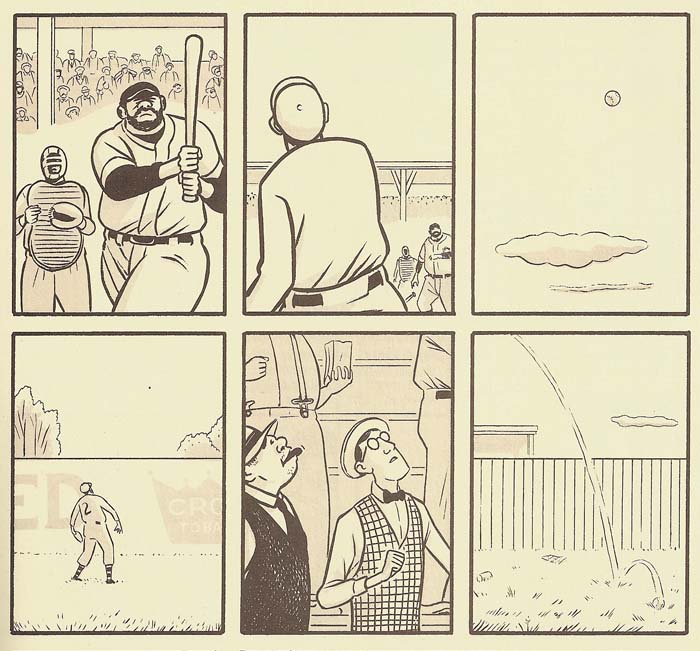

The atmosphere of a baseball game is built-up through images of the park, crowd, and dug-out, with managers flashing signs. The panels are not focused solely on a star or a primary action; a roving eye, as seen in many manga, provides a greater sense of environment than seen in Gotto. For instance, this evocation of a home run in 6 panels (the panel at the end of preceding page shows Henry, the batter, connect with the ball) really makes the reader see the height of the ball along with the players and crowd. Notice how the ball appears at the same place in the composition for both panel three and panel four, only changing in size. Also note the Peanuts-like composition and style in the sixth panel.

Sturm’s style has a certain minimalism to it. Less realistically rendered than Gotto or someone like Jason Lutes (another comic artist whose primary genre is historical fiction), but less iconically cartoony that Seth or Chester Brown. His work bears a relation to Jaime Hernandez in its (lack of) detail and geometric forms but with a rougher, less clean line. He frequently leaves out backgrounds, bringing them in when appropriate for the action. Note in the strip below how the focus starts on the batter, then the background (catcher, umpire, crowd) is brought in for the second panel to provide context, and the third panel drops out the crowd to focus on the pitch call.

Sturm’s depiction of the game is quite excellent and he avoids the necessity for intense non-stop great plays and unrealistic achievements by using the game as a vehicle for themes beyond the game itself. If I find the themes a little under-developed, the baseball is rich, well-paced, and visually exciting.

We’ll end on this lovely strip. The ball rises in the first two panels and then is just slightly dropping in the third, so simple, yet so evocative.

Addenda:

1) French bande-dessinée site, du9 has an interview with Sturm from while he was working on this book that has some relevant passages:

[Sturm:] Basically, the book is about identity. In all these stories I’ve been telling, I’ve been struggling with the idea of America … a country that has very quickly manufactured an identity for itself, myths for itself … and with the Jews there’s this tradition that extends before the concept of America existed. I’m thinking about the construction of identity of American Jews, and in the story I’m curious about how the media amplifies stereotypes.

What I also want to do with this book is just make a really good baseball comic. I like sports, and it’s been challenging trying to orchestrate the rhythms of a baseball game in comic form. The Japanese do it well.

Eli Bishop: Well, two things you really have not seen a whole lot of in American comics are sports and history. I really can’t think of any examples of sports comics.

JS: There’s Cottonwoods [sic], which was a comic strip from the 1950s by Ray Gotto; it was reprinted in a collection by Kitchen Sink. It’s really beautifully drawn, but a little stiff and hampered by its daily format. Lots of forced dialogue: “Hey, Cotton’s going to steal home!”

Some of the technical challenge of this book is not to have this phony voice-over — which does deliver a lot of useful information to the viewer. So I’m trying to figure that out … I don’t want every at-bat to last ten pages. I’m planning on using a voice-over narrative.

2) An excellent review of the book by Charles Hatfield in Indy Magazine.

Previous Post in my baseball comics series: Cotton Woods by Ray Gotto

Next Post in my baseball comics series: Satchel Paige