Cotton Woods by Ray Gotto

Cotton Woods by Ray Gotto. Introduction by Max Allan Collins. Kitchen Sink Press, 1991. ISBN: 0878161457.

Baseball month starts with this classic comic strip from the 1950’s, Cotton Woods, in an out of print collection from Kitchen Sink which covers a selection of the strips from it’s start in the summer of 1955 through the last strip in July of 1958. While the strip is primarily a baseball strip, the protagonist played other sports (football and basketball, maybe others) during the off-seasons. The editors of this volume have left out all the non-baseball strips, which account for about 5 months out of each year.

(Cotton Woods, shortstop, narrowly dodges an attempt to spike him. A great example of Gotto’s dynamic baseball action scenes (and check out that cloud of dust). Take note of the crowd, too.)

The strip follows the life of Cotton Woods, a young man from the “mountain village” of Lonesome Gap, NC. Early on, he enters the minor leagues and quickly becomes the regular shortstop for the fictional major league team The Ducks. Back at home he has a mom, a younger brother (who often is injured or ill), and a missing father, who has disappeared before the story starts. At one point, the father turns up as an amnesiac trying out for Ducks, but quickly disappears. Later, he is in Mexico running away from some men, and the sub-plot remains unfinished. Cotton’s home town girlfriend is called Candie (and yes, there are a few meetings where a panel’s sole dialogue is: “Cotton!” “Candie!”) who is always waiting for Cotton to have enough money so they can marry. Cotton is aided by the village’s Sheriff who not only continues to search for the missing father but is also a former baseball player who just happens to be a friend of the Ducks’ manager. On the team, Cotton’s roommate and friend is Cyclone Clooney, a big country bumpkin who’s always chewing on a piece of long grass.

The plot tends to focus on the sports: games, the pennant race, injuries, rivalries, records, spring training, etc. It occasionally strays to subplots such as Cotton and Candie’s romance (including a few clichéd missed connections and misunderstandings), Cotton’s missing father or little brother being in trouble again, as well as Cyclone’s misadventures (mistakenly arrested for gambling, an unbelievably dumb wife). There’s nothing here that is particularly novel or inventive, everything falls into expected categories for a sports drama. Gotto does not stray far from conventions of plot or characterization. Cotton doesn’t always come out on top, but he does most of the time. The Ducks don’t always win, but they have a lot of miraculous turns of event. Cotton’s team never wins the world series and his marriage to Candie is constantly deferred to another day. But most of the time, whatever is needed comes just in the nick of time (money, a hit, a replacement player).

On my second read through this volume it occurred to me how much Cotton Woods is like a superhero comic. Instead of fighting crime with amazing powers, Cotton plays ball with extraordinary skill. No one steals home as often, gets as many home runs, hits as well, or fields as successfully as he does to beat the enemy/other team. His sidekick Cyclone is not quite as amazing, but he’s close, lacking only the same intelligence as his partner. He’s got a regular, small cast of supporting characters, a few revolving opponents, and he even has a uniform. It’s probably a stretch, but it reads in that same black and white, simple answers style of older superhero comics. But, I don’t (always) expect great literary quality from my comics. Other pleasures can be found in these strips.

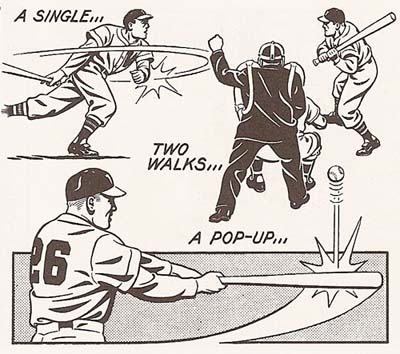

(This early strip (click on it to see it in a larger size), showcases a number of Gotto’s tropes: silhouettes, longshots of the field, extremely foregrounded baseballs, clouds that seem to lay on the ground rather than in the sky, and that ever present burst that symbolizes the impact of bat and ball.)

Gotto’s artwork exists somewhere between the “bigfoot” style and the photorealist style, but closer to the photorealist (we might just call it realist). His work is more realistically proportioned and rendered than the former and more expressive and less detailed than the latter. He wavers between the two at times, to the strip’s detriment. Cyclone Clooney is too often drawn goofy and exaggerated, while many of the action scenes have the stiffness of the photorealistic style without the lush rendering (I imagine there were photo references involved). Gotto has a number of visual tropes he tends to repeat over and over again, like silhouetted characters (often extremely animated and expressive), a really large baseball in the foreground (with a player behind it about to hit, catch, or throw it), clouds (of both the sky/rain and the dust/dirt types) that seem to rise up from the ground, a background of radiating lines (like a sunburst almost), and the pointed star-like shape that represents some kind of hit action. Besides these stylistic representations, there are a great many occurrences where whole panels are reused, usually with just the text edited (I counted one panel repeated at least four times, many others two or three, and that’s just from paging through looking for images to scan).

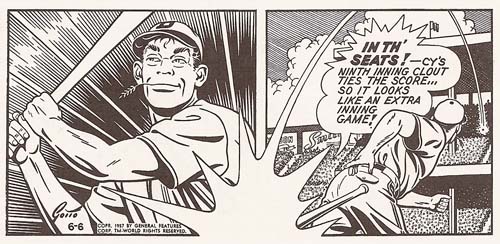

(These two panels not only showcase the oft-repeated burst of impact, radiating (speed?) lines, and traced path of the ball but also a wonderful visual panel transition.)

The depiction of the game is very much focused through Cotton and limited by the space of the comic strip. There is little sense of the overall game, just the occasional score, inning, and chance for clutch hit or a glaring error. Even when Gotto decides to bring a pitcher in as an opponent with a name (for the most part, the players on both sides of the games are nameless and faceless), he captures little of the tension between pitcher and batter, which is one of the biggest parts of the game. Admittedly, I’m sure this has as much to do with space as any predilection of Gotto’s. You could spend the four panels of a day’s strip building up tension between pitcher and hitter, but it probably wouldn’t be very exciting in the serialized format. Because of these limitations, Gotto’s has to hit high points every day, every 2-4 panels, and that makes for a skewed representation of the game. Big hits, stolen bases, dynamic catches, these are not only, ostensibly, the most exciting parts, they are also the most visually dynamic parts of the game. Gotto is skilled at showing those dynamic aspects of the game, composing images for clarity and visual impact.

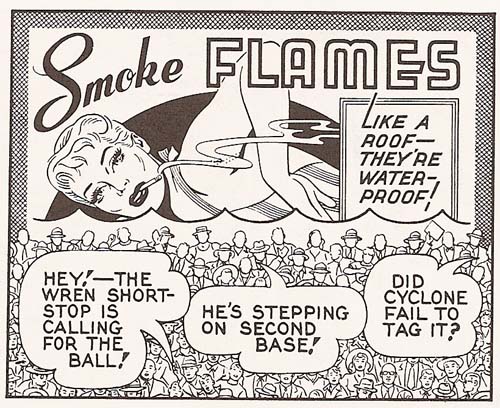

(The crowd as chorus, and what a crowd! The amount of detail in there is crazy. The women on the billboard is a plot point, fwiw.)

Gotto uses a few narrative tactics to move the games along in a speedy manner, so he can focus on the highlights (in some sense, the games in Cotton Woods are like the Baseball Tonight version of games). He frequently makes use of a kind of Greek chorus of spectators or announcers (it’s hard to tell sometimes) to let the reader in on events. This is often a chance for Gotto’s to showcase his skill with backgrounds.

(These wonderful geometric buildings act as a backdrop for a between games commentary by the fans.)

Sometimes he uses a montage image where a few small panels are crowded into the space of one normal sized panel. The example below is a nicely composed combination of three actions in one.

Other similar devices include the newspaper headline montage and the large scoreboard panel. His use of silhouetted figures squeezes a lot of characters/information into a small panel. They make for an extremely pared down visual image but are skillfully done to not only let the reader identify characters (when necessary) but also show posture and expression.

(Great silhouettes. In contrast note the detailed wood grain.)

The two panels above–the end of one day’s strip and the beginning of the next day’s–provide an example of Gotto’s in-game narrative tension. The first panel is also a beautiful and simple composition, while the second is a great example of visual depth. Gotto, as these many panels attest, is very skilled at filling his panels. Through compositional tools like the layered panel above (fore, mid, and background) he creates a certain density to his panels that adds to the realism of the images.

Cotton Woods seems to be little known. In his introduction to this collection Max Allan Collins notes its omission or slighting by a number of reference works on comic strips, while, right now, I note the lack of hits in on a quick Google search (mostly stores selling this book and news items on Gotto’s death in 2003).

While I found Cotton Woods to be narratively average, Gotto’s art and use of the form is skilled and worth examining. His compositions in particular are often brilliant, and at his best times, the baseball scenes are visually exciting. His representation of the game itself is limited in many ways, focusing so much on the “highlights” that little else gets through, but one can forgive him this because of the daily strip format.

I’ll leave off with one more dynamic image.

[Edit: I forgot to mention my thanks to Abhay Khosla for pointing me in the direction of Gotto’s work.]

Next post in the baseball series: The Golem’s Mighty Swing by James Sturm