Le Tricheur by Ruppert and Mulot

This post originally appeared at The Hooded Utilitarian as part of a roundtable of eurocomics.

The comics (or should I say bande dessinee) duo of Florent Ruppert and Jerome Mulot have made only two appearances in English: a two page spread in Kramer’s Ergot 7 and also a short comic (“The Pharaohs of Egypt”) that was translated at the Words Without Borders site. The latter does give a decent example of their work: long strings of word balloons, protagonists that tend to be less than savory, long sequences of McCloudian “moment-to-moment” transitions with a close attention to body language and movement, dry humor, and layouts that mix really large panels with long sequences of small panels.

I first learned of their work from Bart Beaty’s column at The Comics Reporter where he’s raved about their first two books Safari Monseigneur and Panier de Singe. Le Tricheur (L’Assocation, 2008) is their fourth book. In comparison with the earlier works of theirs I’ve seen, it is a fairly tightly organized narrative set within a detective/police/heist genre framework. The story is told non-linearly through multiple timelines. In a timeline that is in the “present”, a police detective interviews four characters: a private detective (“Short Hair”), an art collector (“Batman” because he wears a Batman shirt), a gallery owner (“Tie”), and his niece (“Handbag”). (Yes, all the characters are given names based on some aspect of their physical appearance.) The longer parts of the book take place in an earlier time and show these characters and their companions through a sequence of actions that are part heist, part revenge play, part art project. The logic, meaning, and interrelation of all the events in the story reveal themselves slowly. Each time I reread it (I’m at my fourth or fifth time through) more elements click into place, more layers start to make sense (admittedly, part of this may have been the accretion of vocabulary words as I looked them up and began to remember them).

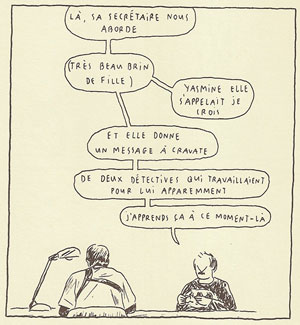

The police interview scenes provide the only dialogue or narration in the book (excepting the final epilogue). Ruppert and Mulot make use of long strings of word balloons floating above the characters in tall panels. While most comic artists, when using long conversations, try to mix in changing views of the characters or setting and attempts at body language or facial expression, here, the dialogue is the focus. The characters serve as little more than indicators of who is speaking in the panels. One interesting use they make of these long strings of word balloons is branching off a balloon that acts as a kind of aside to the main string of dialogue.

An “aside balloon”. This is one of the smaller dialogue panels, most are much taller (this is an unusually tall book).

Mixed between these conversations are longer scenes taking place previous to the police interviews. These scenes are told without words of narration or dialogue and tend to use a large number of panels to show characters acting with great detail. Where the interview scenes are all dialogue, these scenes are all action. I say “action” more in the sense of movement and acting than in the “action movie” sense, though, this being a heist type story, it does feature its share of violence (and one completely absurd gun fight).

Most of the action scenes have the quality of animation: using numerous small panels in a sequence of unvarying composition where the only change is the movement of the characters. The artists attention to body language and posture is impressive and expressive, particularly in light of the complete lack of facial expressions. You see, the artists don’t draw faces. The characters all have a kind of wide V line on their face, like eyebrows except more in the center. This cuts off the possibility for facial expression, putting that much more emphasis on the body language. (It also tends to give all the characters an vaguely angry look.) The expression possible without facial expressions or close-ups (they don’t use them) or even variable angles (none of those either) on the characters is quite impressive, all due, no doubt, to the body language in the drawings.

The viewpoint on the characters is set at a consistent visual distance: they are always the same size on the page. When it is necessary or desirable to show more of the background or set the scene, the artists simply enlarge the panel, including the use of the unconventional (in the West at least) “L” shaped panel (see below). This changing panel size on a fixed scene emphasizes the sense of the panel as a window on the world, a small cropped segment of vision which hides all that is outside of view, all that remains unseen and unsaid. This feeling is quite apt for the story itself which slowly reveals flashes of motivation and background outside of the immediately seen actions. You have to pay attention to the small panels, important events pass in a single panel, and many events are elucidated only through earlier or later events/words.

Characters (Hat, Handbag, and Cap) stay the same. Framing changes with panel size.

The relationship between the dialogue scenes and the pantomime scenes is vaguely ambiguous. Are the pantomime scenes the visual representation of the dialogue? Are they thus colored by the narrator? Or are they completely separate, objective views of events which gain some elucidation through the dialogue–dialogue which is not necessarily true. The title “Le Tricheur” is literally, “the cheat,” and there is a certain amount of tricking and game playing going on here. As the story unwinds through the dialogue, the majority of the events seen in the book are revealed as part of a grand plan of the gallery owner, Tie. He has hired almost all the other characters and given them orders as to what they should be doing.

Ruppert and Mulot’s drawing style is all thin, almost scratchy lines, reminiscent of an etching (yet without that gray glow seen in works like those of Frederic Coche). They use no solid blacks and very little tone or texture, yet everything has a realistic appearance. Characters are naturalistic and proportional. Backgrounds are rather simple line drawings, setting and re-setting the scenes in large panels, yet only sketched out by a few brief lines in the smaller panels.

I love the way they draw the strip club in this scene with all the lines representing lights.

What we learn (yes, I’m spoiling it for you, you can skip this paragraph) is that the gallery owner is doing all this as a kind of art project, promotion for his gallery, and revenge scenario. Two hoodlums, named “Hat” and “Cap” (I’m translating these names), are hired to perform strange activities on their own or with the gallery owner’s niece (“Handbag”). Many of these activities bear some close metaphorical resemblance to a series of paintings in the gallery which the owner (“Tie”) shows to his “friend” “Batman” (he wears a Batman t-shirt). Two private detectives (“Beard” and “Short Hair”) are hired to follow and photograph the two hoodlums, thus creating a photographic record of their activities. The story culminates with Hat and Cap breaking into the gallery to steal paintings and kill “Batman”, all of which is recorded by the security cameras. In this way, the gallery owner organizes these activities but also creates an inter-related visual document revolving around the paintings in the gallery and the gallery itself, with twofold goal of art production and revenge.

The comic “Le Tricheur” becomes, in a way, another level of this interaction/documentation as if the comic itself is part of the whole series of actions and representations of actions that fill the book, with Ruppert and Mulot as the real orchestrators of the whole scheme. This image of the two artists as schemers fits with the image of them seen in some of their other projects. For instance, for this year’s Angouleme festival they organized a collective project with 20 other comic artist called “Maison Close.” Wherein they created a scene (a house of prostitution), drew all the background images, and organized the participation of the other artist. All the participants (including the two organizers who act as the proprietors of the house) drew themselves (or their comics stand-in (ie Trondheim as the bird-self from his autobiographical works)) into various interactions with each other on top of the existing backgrounds. If you’re interested in see more of their work, you might visit their website.