Phoenix Volume 1: Dawn

Tezuka, Osamu. Phoenix Vol. 1: Dawn (1967). Viz, 2003. ISBN: 1569318689.

Warning: I’m sure there are spoilers.

Also, I added a bit to one paragraph in my previous post on Pheonix about characters who appear in multiple volumes. This was to correct something I said that I realized was wrong.

I’m planning on writing about each of the 12 volumes of this series. I don’t want to recount the plot of all these volumes. I’m more interested in the overarching repetitions and themes, as well as individual pages. It’s only in rereading these volumes in close succession that I began to notice many of these repetitions.

Phoenix begins with an erupting volcano. Tezuka starts with a geologic event. This is going to be epic, he tells us. He immediately shifts gears in showing Disney-esque animals fleeing the scene. They run in fear, then they kind of dance, then they run, then as the ground rumbles they turn into spinning balls which collide into each other. The animals fall into a dazed pile. For those not familiar with Tezuka’s work, you immediately know he’s not afraid to mix in comedy even at the most dramatic moments, and he wears his Disney influence on his sleeve. The story briefly focuses in on a young man hunting the mythical phoenix, whose blood is said to grant eternal life. A character focused on the hunt for the phoenix and immortality is a recurring aspect of many volumes in the series. In this case, the first hunter meets a swift end as we switch to his young brother, Nagi.

A man, a doctor, humorously named “Em Dee”, washes ashore near Nagi’s village and quickly gains the people’s confidence before being revealed as a spy for an invading army. A character from one culture/nation/race/people/class isolated with another culture/nation/race/people/class is another recurring plot line in the series. The tensions between the groups, reconciliation, betrayal, romance, are all explored to evoke both the highs and lows of humanity. In this volume Tezuka gives us numerous examples of this interaction, showing us a negative portrayal of the larger group (war, invasion, massacre), yet maintaining a positive level of interaction at the individual level (love, adopted familial ties, respect). Throughout the series, Tezuka seems to be drawing out his own sense for the evils of authoritarianism through rulers, religions, class, or mobs. I have to wonder at the biographical connection to this and potentially any experiences Tezuka had during World War II. I know almost nothing of Tezuka’s biography, except that he was trained as a doctor, but this suspicions was corrobated by Frederick Schodt in his introduction to Adolf: A Tale of the Twentieth Century:

Tezuka was, nonetheless, adamantly opposed to war in any form. ALthough he grew up with the nationalistic propaganda of prewar Japan, he became a convinced internationalist. Too young to be drafted, Tezuka and other students his age were mobilized to work in factories to support the war effort. But Tezuka was eminently unsuited to this militaristic environment and the Spartan discipline required in this endeavor. Worse yet, his job exposed him directly to some of the worst firebombing of World War II, in which the city of Osaka (and much of its population) was torched by American bombers. The results was a permanent loathing of militarism, whether in Japan or elsewhere, and of what Tezuka called the “ego of the state.” Being struck by an inebriated U.S. soldier on one occasion during the Occupation only reinforced his beliefs.[1]

In this first story, we have the first appearance of Saruta, a name and a face with a very large nose, who reappears throughout these stories as different characters. I make the assumption that Tezuka shows us this recognizable figure across time as an example of reincarnation. The concept of reincarnation makes frequent appearances in the series. Life, death, rebirth. This circle of events, portrayed as a natural cycle, is the life cycle of the phoenix itself: living dying, being reborn in fire.

The obsessive search for immortality through the phoenix’s blood is a contrast with this cycle. Immortality stops the cycle, one remains stuck in one stage. The obsession with immortality is often shown as an evil (or perhaps an abomination), an attempt to subvert nature, and a distraction from living life well. Tezuka is a moralist in his way, yet he does not make easy distinctions easy between what is good and what is evil. Things change. Saruta, in this volume, is first shown as a conquering general, a killer of Nagi’s people. Yet, as the story progresses, our impression of him changes. He bonds with Nagi, seeing him as a son, and revolts against his former ways.

As the story ends we find Em Dee’s son climbing out of a cavern where the family has been trapped for years. This character reappears in Volume 3’s “Yamato”. The first character to directly cross from one story to another.

I want to share three pages that stood out for me as interesting. The first example is a two-page spread (pages 158-9):

These pages have a highly organized structure. Three characters face off: Em Dee, at left; Nagi, in the center; and Hinaku, Nagi’s sister amd Em Dee’s wife, on the right. Nagi has just discovered, after years of believing her dead, that Hinaku has been living and having children with Em Dee, the foreigner who lead to the destruction of Nagi and Hinaku’s village/people.

We can read the page normally, left to right (Phoenix was flipped by Viz to read in a Western direction), but one is also drawn to read it top to bottom. Reading across the rows we have a series of moments. I read the three panels in each row as occurring at the same moment (with the exception of the last two on page 159). We can also read top to bottom to see each character’s shifting progression of body language and expression. Em Dee silently shows his remorse, Nagi shows anger, while Hinaku seems to fight between guilt, subservience, and confidence. Tezuka shows each character in a different way. Em Dee is all facial expression and head movement. Nagi, bursting with anger and energy, is shown full body, and, as he is the protagonist of the story, in full detail. He emotes with his whole body in a highly exaggerated manner. Hinaku on the other hand is just a silhouette. She expresses with slight body movements and no facial expressions at all: turning away, hunched over, looking back to speaking up, even raising her fist as she explains her plan, then lowering it again as Nagi bursts forward into her panel.

Speaking of which, the penultimate row finds an example where we must read the panels in reverse order. Hinaku’s words at the right shock Nagi so much that he bursts left through the panel border into Em Dee’s panel. In the last row, Nagi’s then bursts forward into Hinaku’s panel. These breaking of the borders and crossing over gutters is one of the meta-comical, fourth wall breaking techniques Tezuka uses. He can both maintain the consistent structure of this spread and ratchet up the emotion (albeit in a rather light-hearted way (note Em Dee’s bandaged nose at the bottom)).

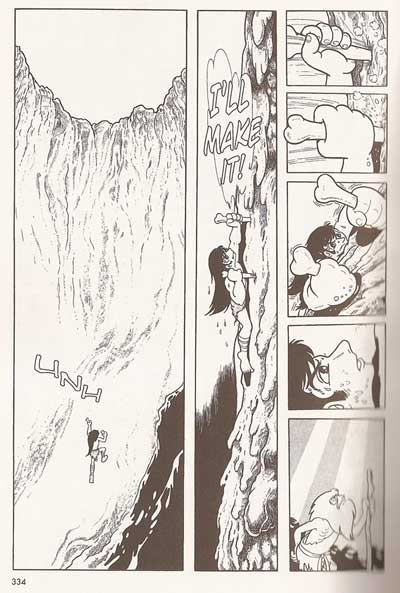

This page (334) shows Em Dee and Hinaku’s eldest son climbing out of the cave/ravine they have been living in for years (the son was born there). This page is most interesting for the way Tezuka has us reading up and down. The movement from panel one through panel two to panel three is an upward movement–lead by the placement of figure and text–that mirrors the son’s climbing. The downward motion of right column is both part of the reading and part of the story. The break-up of panels focuses in on the son’s struggle, slowing the progress of our reading, but also leading the point of view down from his hands (his highest point) in panels three and four. Panel five shows the son from above, a view down at his struggle. Panel six moves us further down to his head focused up. Then the last panel moves down even further to the ground, where Em Dee (now an old man) looks up, mirroring his sons face in the previous panel. That Em Dee is hunched over and set low in the panel intensifies the downward motion and his separation from his son, now high above him.

Next time: Volume 2: Future.

[1] Frederick Schodt. “Osamu Tezuka and Adolf.” Adolf: A Tale of the Twentieth Century. Viz, 1995: 10.