Mary Perkins On Stage

Mary Perkins, On Stage by Leonard Starr. Volume 1: February 10, 1957 – January 11, 1958. Classic Comics Press, 2006. 160 p., $19.95.

Comic strip reprints are coming fast and furious lately. Years of classics are being reprinted in high quality editions by a number of publishers: the formally adventurous strips like Little Nemo and Krazy Kat, the minimalist Peanuts, the rural daily life of Gasoline Alley, the gorgeous art of Raymond’s Flash Gordon adventures, the forthcoming Popeye series, and the just announced Dick Tracy series. Numerous genres are covered, yet one genre and style has been missing, one that was at once extremely popular yet now survives only in the past-their-prime adventures of Judge Parker, Mary Worth, and the girls of Apartment 3-G: the realistically illustrated drama/soap opera.

Charles Pelto comes to the rescue, creating Classic Comics Press to republish Leonard Starr’s classic Mary Perkins, On Stage. The series follows Mary Perkins in a classic set-up: country girl moves to New York City to make it big in the theater. She meets failure and success, romance and rivalry, as she goes about her life, a kind innocent in a world of jealousy and hard truths. It’s probably all that you would expect from such a set-up, and it’s done with verve and healthy doses of (melo)drama. Starr’s sense of pacing is exquisite, each strip recaps, advances, and set-ups the suspense with a movement that keeps one reading and waiting to find out what happens next. Mary seems to reach success and then through various turns of events ends up back at the bottom, an unknown. She finds romance, only to see it falter and end. Such are the ups and downs of the heroine.

But all this would be only so interesting without the realist rendering of Starr’s art. This is the classic realist strip at its best: clothes, interiors, exteriors, and facial expressions are all seen in detail and with a lower level of abstraction than most comics. For the art alone, this reprint volume is a necessary publication for those interested in the history of comics strips. I marvel at the economy with which Starr fills his panels with details, the dynamic strokes that delineate the folds of clothing, the precise geometry that structures the panels and organizes the backgrounds.

Starr’s use of the limited space of the strip is subtly skilled. His compositions work to set scenes, heighten the drama, and provide clear readings of the strip’s events, all the while retaining visual variety (far different from the repetitions of Harold Gray). For a majority of the panels he fills the backgrounds with details of setting, but he knows when to leave them blank so we focus on the characters and their body language or facial expressions. The organization of the characters and their interaction with each other and the background puts the space to use in directing the reader’s eye through the strip in a smooth manner. Starr frequently uses compositions that move a character from foreground to midground and back to foreground across the strip’s three panels. In the strip below–a more unusual example because of the use of three characters instead of the usual two–note the shuffled positions of the three characters. While Mary stays in the middle, the other two shuffle positions from one panel to the next.

(Click on any of the images for larger versions.)

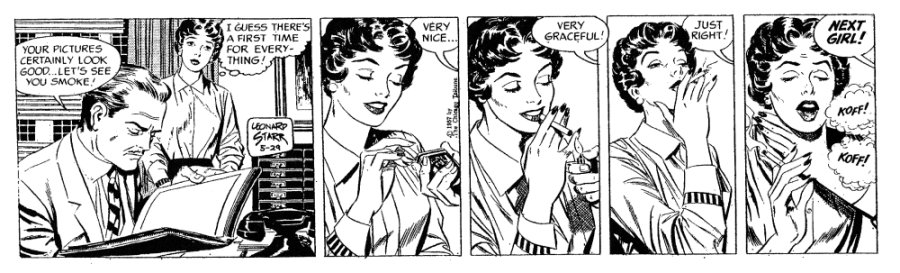

The layouts mostly stick to a three panel strip but Starr is not afraid to vary his panels when the story calls for it. A fine example is in a strip where Mary smokes for the first time as part of an audition and Starr draws five panels, four of which show moment-to-moment movement of Mary, drawing out the humorous event (a non-smoker in the fifties!).

Another unusual composition involves Mary’s ongoing search for work. Two panels: an almost nightmarish collage of heads backing Mary into a corner and then a single unadorned close-up heavy with shadow.

While the strips are usually rather wordy with dialogue, the occasional silent panel (or sequence of panels) is all that more powerful for the shift involved. The silent panel below stresses Mary’s isolation amongst a no doubt loud and raucous crowd, drawn out with the width of the panel and finding Mary at the further end of it.

The book itself is very well produced with a color cover that includes a color Sunday strip reprinted on the back (makes me wish there were a few more color strips (maybe in future volumes)). The strips themselves are printed three to a page for dailies. Most of the strips are taken from Starr’s production proofs and the quality is high for most of the volume, though there is a run (about two months) that had to be reproduced from newspaper archives which look a little squished and have lesser line quality. Walter Simonson provides an introduction/appreciation and Pelto writes an introduction to Starr and the strip.

They don’t make them like this anymore, and while the strips here are just under 50 years old, they have aged well. While these stories often verge (and dip) into cliched narratives, amidst the contemporary comic landscape of self-involved autobiography, superheroes, grotesqueries, literary graphic novels, and the so called new mainstream, On Stage‘s soapy drama is renewed. Reading these is much like the appreciation of a fine classic film from the period. We can see past the sometimes dated storytelling to the art that lies beneath… plus, it’s just good dramatic narrative, well structured, solidly executed.

Volume Two is already expected in November with a greater number of strips/pages. I’m looking forward to it.