Dylan Horrock’s Atlas 1 and 2

Atlas #1 and #2 by Dylan Horrocks. Drawn & Quarterly, 2001-2006.

Comics take a lot of work to create. Excepting the actual idea generation and writing process, the drawing alone can takes hours and hours of work. The big two publishers have the multi-person system (writer, penciller, inker, colorist, letterer) to keep their monthly schedules. A single cartoonist, probably also working on other jobs, may find it difficult to keep up such a grueling schedule. Dave Sim always stressed the need for consistent, regular output in his advice to self-publishers, and I can’t argue with his success. Even at its slowest moments (Cerebus spending issues doing nothing but sitting in a bar), I always knew another issue was just a month away. Many other less-frequently published serializations have much less success with this type of slow pacing. Seth’s Clyde Fans, moves at a glacial pace both in narrative time and publishing time. One wonders if the economics of serialization (regular pay rather than waiting for a complete book) makes the irregular schedule worthwhile (how many, like me, keep buying the issues instead of waiting for the book).

Dylan Horrocks’ Atlas #1, a much anticipated follow-up to his highly successful Hicksville (see my review), came out in 2001 from Drawn and Quarterly. The 100 page comic has 66 pages of the beginning of the story “Atlas.”

“Atlas,” subtitled “A Life of Emil Kopen,” returns readers of Hicksville to some familiar territory. Divided into two parts, the first is labeled “0” and begins with “Dylan Horrocks”, the elusive (autobiographical?) character from the prologue to Hicksville, being questioned by officials of the fictional country of Cornucopia (very Eastern European with its city of “Crieste,” slovak style language, and communist style oppression) about his interviews with Cornucopian cartoonists, including Emil Kopen. “Horrocks” is vaguely threatened and told to leave the country on the next train. We learn that mapmaking is illegal in the country and that Kopen considers himself a cartographer (you may remember that scene from Hicksville).

The second part brings back Leonard Batts, the comics journalist who is one of the protagonists of Hicksville. He visits an old colleague and tells of his new project to write a biography of Kopen. He gives a very brief overview of Kopen’s work. This section is preceded by a brief image of a soldier. A woman, angelic, almost floating, stands behind him, her hands covering his eyes. She whispers into his ear in an untranslated Cornucopt (one assumes based on the earlier use of the alphabet by the interrogators of “Horrocks”).

(I just really love this cloud drawing from the middle of Atlas #1.)

The first part is done in a steady four panel grid that speedily moves through the interrogation scene. These pages are almost exclusively talking heads with no backgrounds. The interrogators faces are unchanging and “Horrocks’s” shifts from casual concern to real distress. In this 24 page sequence the words are the focus and one easily breezes past the images. This might be interesting if some sort of pattern of repetition or organization were apparent, but instead the whole sequence is visual numbing.

The rest of the story is all single panel pages. The large open pages are effective in the introduction and the strange sequence with the soldier, but the section with Leonard Batts seems needlessly stretched out. Horrocks art (in this issue) is not so lush in detail or beautiful in linework that one feels the desire linger over large images. His style is simple, effective but simple. As such, the single panel pages that show Batts conversing with his colleague feel large, empty, and slow. It takes away the ability to change timing and pacing in the comic. The larger panels that precede it, which would benefit from the large size, are lessened by their uniformity to the rest of the sequence, lacking the visual impact of relative size that would be present if Batts’ sequence were done with smaller panels.

Five years later–a reader would not be faulted for having forgotten all this–Atlas #2 is published. The back-up story “Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen” provides interesting work for the reader in interpreting the long silence. Sam Zabel was also a main character in Hicksville. He is a cartoonist, struggling to make his living (and his art) in an uncompromising way. The story (part 1 of another serial) shows us Zabel, unable to draw, hopelessly blocked. To make his living he writes “Lady Midnight” comics for a major publisher (the same character that appears in Hicksville). He is depressed, unexcited by comics, novels, film. He escapes into lush neo-classical images downloaded from the internet. The step to autobiographical interpretation is a short one. In between issues of Atlas, Horrocks wrote Batgirl for DC (and a Vertigo book) and seemingly produced very little else.

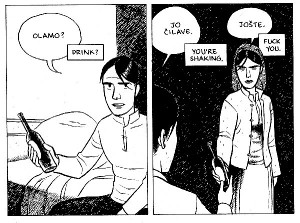

The second issue’s installment of Atlas has only oblique connections to its predecessor. The table of contents gives us the “Story so far: Leonard Batts wants to write a book about cartoonist Emil Kopen – but first he has to find him. Meanwhile in Cornucopia…” This at least lets us know the setting and time of the story here. A woman visits a man, who seems to be in hiding. She brings him a bag of something. He wants to sleep with her, and she rejects him. She leaves.

This chapter uses more variation in page layouts: from one to four panels on each page, two being the average. While this may not seem like much, it makes a big difference in the pacing of the story. There is more of a sense of slowed and speeded up time in this section than in the sections in Atlas #1. There is more boduy language and setting in this section, too, rather than just talking heads.

Horrocks art style has changed ever so slightly between issues (similar to the slight changes apparent over the course of Hicksville). The art has less appearance of crayon or dry brush use. The lines are more consistent and precise, and shading is accomplished with a dense parallel hatching. (See the small samples above.)

Atlas #2 does improve on Atlas #1, though the connections between make one wonder at any shifts in plans over the course of the hiatus. But, even in its improvement, there is still very little meat to the issue. The story hardly moves along at all. Unless Horrocks can keep up a rather steady pace with future issues, he may lose the interest of his audience. When a story is doled out at a such a slow pace in such small chunks, one might as well wait for the collection.