Panels & Pictures: One Page

Since the theme for this month is short stories, I thought I'd take a look at a short comic. It's an old (well, it goes back a few decades) literary practice to do a "close reading" of a work, usually a poem. You don't see many close readings of comics, the most notable exception being John Benson, David Kasakove, and Art Spiegelman's "An Examination of Master Race" on Bernard Krigstein's short story "Master Race". Jaime Hernandez is one of my favorite comic artists, a master of the (mostly) unique comic form of the serial short story.

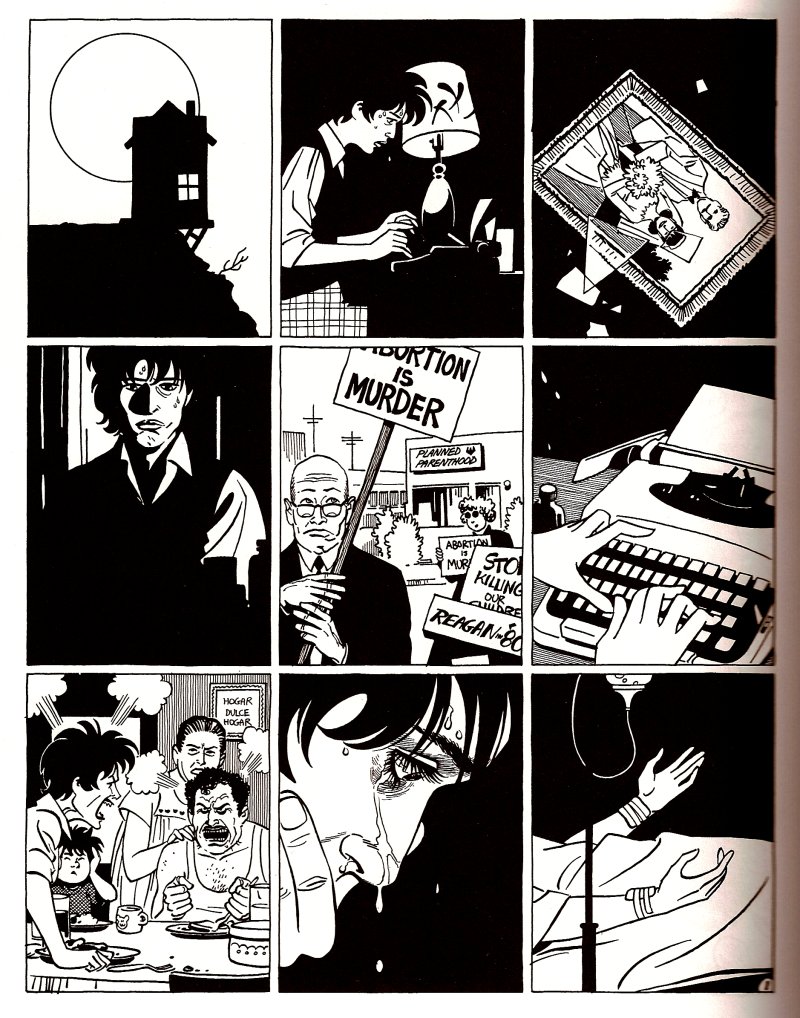

Going through a whole story would take some time (and space), so I'm just going to look at the first page of Hernandez's "Flies on the Ceiling," which you can find in volume 9 of the Complete Love and Rockets (entitled "Flies on the Ceiling") or in the Ivan Brunetti edited Anthology of Graphic Fiction. The first page is a brilliant example of a comics narrative's ability to intermingle timelines and effect a concision in narrative explication. In nine panels he tells a short story within the story.

Panel 1: A black silhouetted house leaning over the edge of a cliff with a large circle moon behind it. Black is important throughout the story, not only visually — Jaime is a master of the spot blacks — but also thematically. The house teetering over the cliff can be read as a metaphor for Isabella's (the protagonist) mental state. The black edge of the cliff leads the eye to the next panel, and the white background on the right side of the panel contrasts nicely with the black background in panel 2.

Panel 2: Isabella sweating over her typewriter in the dark. The despair on her face (even without the sweat) is palpable with only a few lines. The juxtaposition from the first panel to this one lets us assume that Isabella sits inside this teetering house. (For the reader who's been following the series, we can also tell, by Isabella's appearance, that this story takes place in a "past" of the ongoing narrative.) In the minimal style of Jaime, even a small detail like the lamp next to Isabella is important. In this case, the tilted shade adds to the feeling of disequilibrium, an echo of the teetering house. The figure's leaning and the tapering white of the objects on the table lead us forward to the next panel.

Panel 3: The transition from the previous panel to this one starts a page-long sequence of back and forth transitions from an exterior present (Isabella at her typewriter) to an interior (or possibly written) past. Here we see a visual trope, the wedding photo in its broken frame, an obvious (and as such, effective) stand-in for a divorce (how better to show that in one panel without words?). The photo is upside-down on a black background, adding to both the off-kilter nature of the previous panels and the darkness. The placement of the photo also leads the composition from the the left side of the panel around and down, taking the eye back to the next tier of panels. We can assume the woman in the photo is Isabella; the man appears to be an older man (moustache and white hair).

Panel 4: Back to Isabella, a little larger in the panel than before, though even more of the panel is black. She looks stunned and motionless. The white in this panel starts at the top left and moves to the middle right, leading us to the main figure in the next panel.

Panel 5: Protesters with anti-abortion (and pro-Reagan) signs in front of a Planned Parenthood office. The "Reagan in '80" sign subtly clues us in to the narrative past of this moment (Jaime's stories ostensibly exist in the present, and this story was published originally in 1989.) Again, this is a wonderfully economic way to signal an abortion, Isabella's we assume. The use of type going off-panel into Isabella's left hand (in the next panel) leads us across the panel and onto panel six.

Panel 6: Back to Isabella, just her hands and the typewriter. Is she typing the story of the other images (divorce, abortion, etc)? That's what I assume. The position of the hands in this panel show movement; time is passing in this narrative present. The two hands in their positioning, like the picture frame in panel three, lead the eye back around to the next tier of panels (from her left hand up to the typewriter and then back down the right hand).

Panel 7: Isabella in the past at, we can assume, her family dinner table, with a father, mother, and younger sister. Isabella and her father are yelling. Jaime uses a classic comics idiom of steam shooting out of the characters' heads, which adds a slightly comic (as in classic comics and as in funny) edge to what is otherwise a very dark page. The four figures are crowded into the panel, their heads all very close in the composition, which gives a feeling of claustrophobia, adding force to the "daughter fighting with the parents" concept.

Panel 8: Isabella again in the present, her profile takes up half the panel, her hand over her mouth, tears and sweat fall. The sequence of panels 2, 4, and 8 ratchet up the despair in Isabella's face. These panels make up a discontinuous-in-page-space but continuous-in-narrative-time sequence (as does the sequence 3, 5, 7, 9.)

As the the composition move closer to Isabella's face, the reader is moved metaphorically closer to the character emotionally. The page is partly a process of moving us into the character who will be the focus of the story (and who, previously in Hernandez's work, has been seen only from the outside.)

Panel 9: Two arms in the air and a torso covered by a sheet. An IV stand and prominent bandages on the wrists create an economical way to signify a suicide attempt. Unlike the two previous panels that ended a tier on this page, this composition does not move around and down. Instead, the position of the arms in relation to the sheet pushes us forward and up; in this case, to the turn of the page. (The movement from one page to the next, particularly in a case like this where the reader is turning a page (page one is the recto) is not often utilized in comics. Hergé was particularly conscious of this reader movement and worked it into his Tintin stories.)

Six of the nine panels are predominantly black, which gives the page as a whole a very dark presence, emphasizing the narrative therein. Even without reading the panels, just looking at the page as a unit unto itself, it conveys a mood, an oppressive black.

As I mentioned, we have two intertwined narrative lines going through this page. It is a brilliant use of what might be called cross-cutting or parallel editing in film theory, where the film jumps back and forth between two narratives (the distinction being, I believe, that cross-cutting involves the movement between two simultaneously occurring narratives, and parallel editing is not necessarily simultaneous). The pacing of each of these narratives is different. Narrative one, the present in panels 2, 4, 6, and 8, seems to exist at both a small moment in time (Isabella is just sitting, typing, and crying) and outside of time (there is no real indication of how much time passes). Narrative two, the past of panels 3, 5, 7, and 9, compresses larger events into a single panel and then moves across a longer period of narrative time from one compressed event to the next.

The different speeds of these narratives give a real visual metaphor for the past "catching up" with Isabella. As the present moves slowly forward (or hardly moves at all), the past comes rushing forward at a bounding pace. This prelude to the rest of the story (page two is the title page) acts out a microcosmos of both this story and the general character arc for Isabella in the rest of the Locas stories).

[Originally published at: http://comixtalk.com/panels_pictures_one_page]