The Book of Genesis Illustrated by R Crumb

Crumb, Robert. The Book of Genesis Illustrated. New York: W.W. Norton, 2009. 224 p. ISBN 9780393061024. $24.95.

I’m not a fan of Crumb or the Bible. I thought I’d put that out there first. So it’s not surprising that I didn’t enjoy The Book of Genesis Illustrated. I didn’t enjoy it and found it a bit of a slog to get through, yet from a formal point of view, it is interesting in its own way.

That the book is called “The Book of Genesis Illustrated” and not “The Book of Genesis Comics” (“The Comic Book of Genesis”?) speaks to a terminological divide in the world of comics. This work uses the complete text of Genesis (with apparently a very few minor alterations by Crumb) in conjunction with images in panels. In his introduction, Crumb writes that he approached it as a “straight illustration job.” I must erect a straw man, but it is often argued that illustrated texts are not comics (for a great argument for illustrated texts as part of a larger comics related field see Harry Morgan’s Principes des littératures dessinées). Taking an existing, self-contained literary text and adding pictures is considered somehow outside of the field of “comics,” mere illustration. The pictures are a supplement, an unnecessary addition.

Take, for example, one of N.C. Wyeth’s illustrated works: very few would consider it “comics.” He has added a few images to an existing novel. Yet, this is what Crumb has done. Using the Bible’s text as a ceaseless stream of narrative captions and narration filled (pseudo)panels, he has added some pictures. Of course, Crumb has added a large number of pictures (more than I care to count), while Wyeth adds a rather few number, not even one a chapter.

I can’t help but consider R.C. Harvey’s visual-verbal blending (see The Art of the Comic Book). Here we have a book that can be read as text without the pictures, that is its original form after all. From Harvey’s point of view is Crumb’s Genesis all that different from Foster’s Prince Valiant, which he refers to as an “illustrated novel.” Though I guess, with the right amount of “closure,” one could read a lot of comics without the text or without the pictures (depending on the work).

In both cases, by adding images to a text, the artist is creating an interpretation of the text, adding their own views (in a literal sense) to the words. These works are readings of the text, oddly, readings that are pictures. In Wyeth’s case these views are primarily (I suspect, I haven’t made a study of them) visualizations, his idea of what characters, settings, or events look like. Crumb does this, but also adds more thematically interpretative content as well. In the commentary section at the back of the book, he discusses some of these interpretations.

Some of Crumb’s interpretations are less his own than just old cliches. God is portrayed as an old white guy with a long white beard. Adam and Eve are rather Teutonic looking white folks. The garden of Eden is a deciduous forest and the fruit of knowledge looks like an apple. I’m not a Biblical scholar, so I have no idea where his visual interpretations stray from convention or history, but the above examples seem fairly wrong to me.

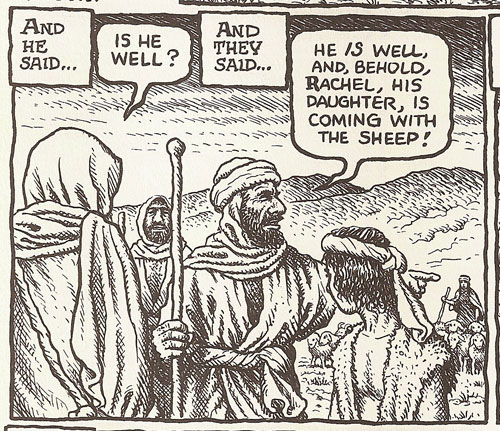

Crumb’s use of the full text of the book does not do him any favors in terms of readability, particularly in the way he slavishly sticks to the text as narration. He even maintains the use of “he said” or “she said” in the text, leading to stupidly awkward panels with a “he said” narrative caption accompanying a word balloon. This type of text usage puts me in a mindset as I read that the images aren’t really that important. Perhaps it is just Crumb falling into the all to common trap of taking the Bible too literally.

The narration is non-stop, without pause. I’m not sure there are any panels that are not accompanied by a narration caption or at least a word balloon quotation. There are no silent images, he does not take his interpretation so far as to create movement or scenes from narration that is often just summary. In this way it is much like an old comic book from the fifties. In fact, the more I think about it, the more this book reads like a comic book from what is probably the time of Crumb’s childhood. The dust jacket hearkens back to some former age of comic books, another case of comics nostalgia by one of its most praised practitioners (see Clowes, Seth, Ware). The page layouts, the heavy and often redundant captions, the breakdowns that are more summary than scene: all of this feels and looks so retro. Crumb’s style does not fit in this regards, it is just his usual style of cross hatching which is quite different from popular comics of the fifties. The style does work for this book to a certain extent, giving a sense of earthiness to the times. Though Crumb’s figures are all rather similar looking: his large physiqued women and the smaller, frazzled men that are only a few centuries away from a self-portrait.

In reading the book, I felt a distinct lack of affect. Perhaps it is due to the literary style of the original, but I don’t feel anything for the characters. Everyone is playing out their singular interest and there is little that shows characters relating to each other. It did not help that Crumb tends to make everyone look a bit crazy in the eyes and mouth. Eyes stare wide, mouths hang open with upper teeth showing. I’d like to see more emotion there.

Yes, I’m pretty harsh on the work, but I’m sure there are enough glowing reviews out there already. The book did have one positive effect: it caused me to take another look at Genesis. I hadn’t reread it since my freshman year at college (for a class), and this reading so many years later only reinforced my complete bafflement at people who claim to believe the Bible literally. You can start with the way there are two versions of the creation story. Did they both happen? Or take a look at the way Cain, son of the first man and woman, leaves his family (after he kills his brother) and then finds himself a wife. If Adam and Eve were the first people and he was their only (living) son, where did his wife come from?

I can look at it in a different light: the creation story is not the creation of everything, but the creation of a specific group of people. It’s their solipsistic creation. They are the only ones that matter, so their beginning is the beginning of everything. Almost all the stories here are about families fighting over land and inheritance and succession. And it turns out this was part of Crumb’s purpose in making the book. A recent report from Crumb’s interview at this year’s Angouleme festival by Mattias Wivel noted:

“Fortunately, there were a few interesting questions from the audience, one of which prompted Crumb reticently to admit that his intention was partly to dissuade people from what he sees as the tribalist worldview of the Old Testament, even if tribalism in a small community, or in music, is a natural and important impulse in us.” (http://www.metabunker.dk/?p=2290)

He was at least successful in that respect. Though, I’m not sure this is specific to his interpretation. And even if it was, with his reputation, it’s not like the people who really need to think about such issues are going to be reading this version of Genesis.

I can accept Crumb’s historical importance to comics, even without liking his work, but this book seems less a successful masterwork of a distinguished elder than a strange curio.