Wordless Novels and At a Crossroads

The number of comics in the “to blog” pile in my office is a little overwhelming. Some are slated for longer appreciations, but many, I suspect would benefit just as well from a quicker look at the highlights or just whatever caught my interest in the work. Or maybe, as happened in this case, a group review of tenuous connection. We’ll see how this goes [Edit: After writing this paragraph I ended up writing two not very short reviews in one. Maybe next time, I’ll actually get through more comics quicker.].

Berona, David. Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels. Abrams, 2008. Hardcover, 256 p, $35.00. 9780810994690.

This book serves as an excellent introduction and showcase for the “wordless books” of the title: picture books for adults featuring single page image narratives that do not (or only rarely for signs and the like) use words. A number of these “novels” have seen new editions in recent years (including a number of Frans Masereel’s woodcut novels, Lynd Ward’s wood engraving books, Milt Gross’s He Done Her Wrong, and the collection Graphic Witness which collects works by four of the authors shown in this book), and this volume features an even wider selection of artists and works. Almost every chapter is dedicated to a single author, providing a very brief biography and then a description of one (or more for the the cases of Masereel and Ward) of their works. Berona’s text is primarily plot summary, with occasional forays into a brief discussion of some formal or thematic element.

An opening chapter offers some context for Masereel’s woodcut books, and a closing chapter points towards the rise of graphic novels and some recent wordless books (Drooker and Kuper). All of the works that are the primary focus of the book were published between 1918 and 1951, which allows Berona to address them as the “original graphic novels” and placing them as comics or at least in the comics family. This relation is not delved into beyond the concept of influence (early comic strips on the artists seen here, the artists seen here on current comic artists). And while I’ve probably heard enough on the “is it comics” front, the topic seems almost necessary in a book using “graphic novels” in the subtitle. All these works almost completely eschew panels, word balloons, and image-text relations all of which have been at various times posited as essential elements of comics, which quickly leads one down the definitional road.

All in all, Berona’s text is more descriptive than critical, serving primarily as annotation and context for the images, which are the primary content of the book (taking up I’d guess 80% of the pages). The images presented are crisp and clear and showcase the work well, providing pages and pages of imagery. While the text gives the narrative context for the images, I would have liked to see some kind of page indicators. It is impossible to tell if any of the selected images appear on adjacent pages. Out of this context, the reader cannot get any idea of how the artists addressed the issue of visual and narrative transitions from one page to the next (something that would be interesting to examine). I’ll have to look for that in the complete works, I guess.

While I am familiar with Masereel’s work (I have a few of the very nice hardcover volumes from Shambhala) and Ward’s work, a number of the artists in this volume were pleasant discoveries: Otto Nuckel made lead prints using a multiple tool (making more than one line at once like a rake) to create images that have a geometric cross-hatched screen appearance that is quite unusual (see above); William Gropper used a splatter effect for tonal variation and to delimit “picture balloons” (a helpful term for word balloons that use images instead of words) (see below); and Istvan Szegedi Szuts’s work has a minimal Japanese ink brush quality that is lovely. If you haven’t seen Masereel’s and Ward’s work, both are masters at composition and narrative density. Masereel’s woodcuts have a starker high contrast flattened style, while Ward’s wood engraving make use of tone and depth for a detailed realistic style.

So, while I would have liked to see more in the way of critical attention to the work, the history lesson and the art reproductions are enough to make this a valuable book for browsing and a pointer towards the complete works discussed.

While discussing Otto Nuckel’s Destiny, Berona pulls out a quote from H. Lehmann-Haupt’s review of same that is worth a moment (97):

…the pleasure is more subtle [than cinema], for we are alone in this theater and audience and operator are one person. We can make the story run quickly, we can even skip but we can also stop altogether. Then suddenly it is not so much a piece out of a story that counts, but an individual picture with its own particular qualities. This is where the superiority of the picture novel comes in.

The tendency to linger on a single image is, I believe, more prominent in a work that uses only single page images. The physical primacy of the page as organizing unit gives it a certain power, and when a single image covers that space, a reader (this reader at least and I suspect many others) is more likely to linger on the image. This may not amount to more time spent on the page than if there were six or nine panels (and perhaps still even less time), but it is more time spend than on any single image in a more complex page layout (mise en page). While single uses of such images are frequent (title pages, splash pages), a consistent use across a whole work is considerably more rare in comics proper (to take a more conventional sense of comics), in fact, the use of single page images throughout a work is one index that is often used to say “this is not comics.” An argument one (but not me) might apply to the wordless novels of Berona’s collection or to more unusual works like Martin Vaughn-James’s The Cage. One might also include:

Williamson, Kate T. At a Crossroads: Between a Rock and My Parents’ Place. Princeton Architectural Press, 2008. Paperback, 144 p, $19.95. 9781568987149.

Williamson’s book is an autobiographical account of the 23 months she spent living at her parents’ house after graduating from Harvard and spending a year in Japan. She moves home to work on a book, but mostly, as the title indicates, she is at an in between place in her life, not a grown up, not a teen or a student. The concept itself is banal. The protagonist’s problem is at its heart, banal and unexciting, which almost requires that the narrative itself be banal and unexciting. A certain bravery is inherent in even attempting to make a book out of such material. The concept brings to mind a certain kind of straw man independent film about young people doing nothing, but Williamson’s narrative even avoids the perennial backbone of such films: love, sex, and romance. Even her career/artistic ambitions (the book she is writing) is featured only briefly and never discussed as a struggle of any sort.

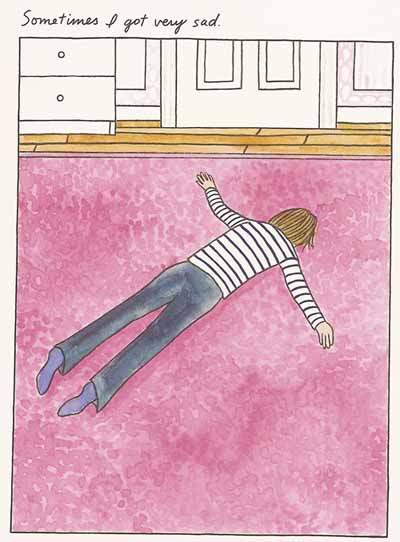

Williamson effectively captures a feeling of being “at a crossroads,” a listless time of sitting out of place in the past of childhood yet not getting on with adult life. We see Kate during holidays, portrayed as isolated or ill fitting (Easter finds her karaokeing by herself). She spends time with the children across the street from her grandmother’s house. The cute boy next door is the peer of a boy she used to babysit. The ways she shows herself filling the time are largely lame and silently sad. The cover image of Kate laying face first on the floor nicely summarizes this. In the book it is accompanied by the text: “Sometimes I got very sad.” Just the list of concerts she shows herself attending is sad in its own way: Hall and Oates, Cher, and Chicago (all, in their way, part of the struggle to stay in the past).

Williamson pays careful attention to marking the passage of time. Two page spreads show close-ups of trees, the leaves changing color, falling off, blooming, etc. She shows geese migrating and snow covered yards. Holidays are shown once then again (one page is labelled “Halloween”, another later “Halloween 2”).

At a Crossroads is primarily a book of single or double-page images. The numerous double-page images all bleed off the page, while the single page images are all bound by a border. Multi-panel pages are used, though Williamson never uses more than two or three at a time. The images are rarely used in conjunction with each other to create an ongoing scene. Rather, each, with a few exceptions, are whole scenes to themselves. The textual narration provides the extra details needed for context. The scenes are often grouped together so that we see Kate floating in a pool and a dog sitting nearby, the narration telling us that she spent time dog sitting at a house with a pool. This image takes place in the day, and we turn the page and see, one of the loveliest images in the book, a night sky with a bit of colored light shining from behind a treeline (see below). The narration tells us she spend the Fourth of July floating in the pool with the fireworks going off in the distance. The scenes are related but not directly contiguous. In this way, most of the book is organized.

(Narration continues on facing page (too big for my scanner) “…to fireworks in the distance.”)

Williamson makes occasional use of word balloons, but the primary text is an ongoing narration written in a cursive script beneath or at the bottom of the images. The handwriting adds to the diaristic appearance of the book. A nice complement to the style and content of the narration.

The art itself is interestingly complementary to the content as well. Somewhere between child-like simplicity and grown-up sophistication (to draw a too clean distinction). People are drawn looking a bit stiff and flat though clearly based on some realism (a browse through her website shows a greater skill with drawing people than is seen in this volume). The backgrounds are often an intriguing combination of flat two-dimensional objects and traditional perspective. Her linework is unvarying and at times too ruled out (again a bit of stiffness), but the watercolor are vibrant and add a lushness to the artwork. The colors add a great deal to the images, such as the childish pink of her old bedroom or the changing colors of nature as the seasons change.

At a Crossroads effectively conveys it subject matter in a stylistically harmonious way, but in the end I’m not sure what the experience is worth. I applaud the very banality of the narrative, as if all drama had been excised (or was never there) but on the other hand I wonder if this would be even more effective as a smaller, even less narrative work (just two-page spreads of the seasons passing interspersed with other scene-images). For all it’s diaristic qualities, the narration feels distant and one doesn’t get a great sense of who Kate is. One finds little introspection or examination. Still, I am curious to see what Williamson comes up with next.