Phoenix Volume 3: Yamato

Tezuka, Osamu. Phoenix Vol. 3: Yamato/Space (1969). Viz, 2003. ISBN: 1591161002.

See previous post on Phoenix Vol. 2: Future.

Viz’s Phoenix Volume 3 includes two stories, the third and fourth in the series. This is where the volume numbers and the story numbers will stop matching. Later there will be stories that take two volumes to complete. I’ve decided that instead of writing about each volume individually, I will write about each story individually.

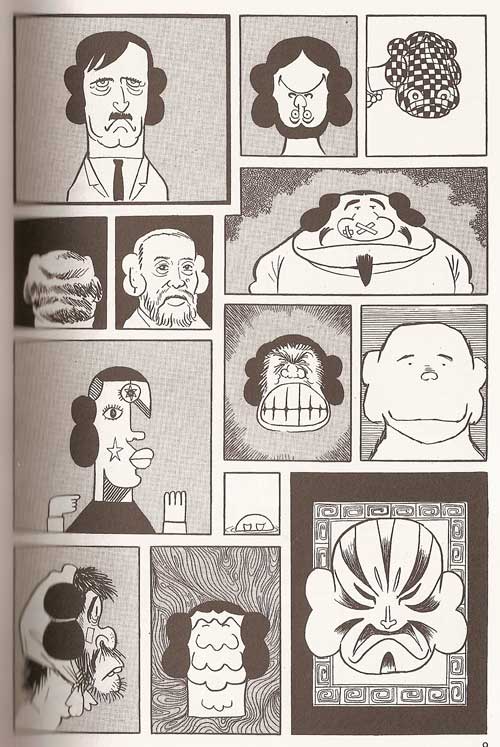

“Yamato” takes place in the past, fifty or so years after the events in “Dawn.” Once again we have a story of warring kingdoms and individuals whose personal relationships fight with loyalty to their kingdom. We first meet the king of Yamato in a wonderful sequence of portraits (by the king’s painters), which Tezuka uses as an opportunity for both parody and pastiche. The king is greatly (and solely, it seems) concerned about his legacy, especially the history of his rule and his great tomb. The history is being challenged by Takeru the “barbarian” chieftain of the nearby land of Kumaso, who is also writing a history which will not portray Yamato and its king in a flattering light. The tomb, a massive construction that will include a sacrifice of many civilians who will be buried with the king, is being challenged by protesters. Unlike many other characters throughout this series, the king of Yamato is seeking an immortality not of body (by drinking the phoenix’s blood) but an immortality in the collective memory through manmade objects.

Those protesting the tomb include the king’s youngest son, Ozuna. This particular aspect of the story is clearly pulling from contemporary events of generational rebellion and protest during 1968, one of the many aspects where Tezuka uses anachronism in an historical story. The king decides that Takeru of Kumaso must be killed, and Ozuna, as punishment or a chance to redeem himself, is sent off on the mission.

In Kumaso, Ozuna meets Takeru, whom he realizes is an honorable man, as well as his sister Kajika, a tough and headstrong young woman, and the phoenix, in whom Ozuna takes much interest. Ozuna sees Takeru consumed by his work on the history he is writing, and Takeru introduces him to the village elder, a man who long ago was given motivation and purpose by the phoenix. This elder is the same young man from “Dawn” whom I showed the page of him climbing: one more crossover character between volumes.

Ozuna and Kajika, predictably, fall in love, and she tries to convince him to stay in Kumaso with her. Faced with these individuals, Ozuna begins to question his purpose in life and his loyalties. At night he swims out on a lake to an island where the phoenix sleeps. He plays a song for it on his pipe (some kind of woodwind). The phoenix speaks to him, asking what he wants. Ozuna does want the phoenix’s immortality granting blood, but, again unlike many characters throughout this series, not for himself. He wants to use it to save the human sacrifices his father the king will make for his tomb. Through a sign of the phoenix, Ozuna is convinced to go back to Yamato.

Before leaving Ozuna kills Takeru, who has just finished his history. He flees, pursued by Kajika. The phoenix aids his escape and allows him to soak a rag in its blood. Back at Yamato, Ozuna is rewarded by being put in charge of the tomb construction, which he quickly subverts into the construction of a playground. When the king discovers this, he locks up Ozuna and quickly dies from the disappointment of not having his tomb completed. The tomb is quickly adjusted to bury the king. Ozuna and Kajika, who has infiltrated Yamato (at first to kill Ozuna but then to help him), are chosen as part of the human sacrifices. With the help of the phoenix blood they, and the other sacrifices, end up buried alive, living for a year (because of the limited amount of phoenix blood each had) under the ground, crying out in protest of the sacrifices.

If “Future” begged the question, how should one live their life, “Yamato” offers some examples to begin an answer to that question. The king of Yamato is a negative example. He is so concerned with his image and building up his empty legacies (a self-aggrandizing history, a huge tomb) that he does not actually live his life. On his deathbed he proclaims his life a “stupid waste” and his last words, “only death cures fools.” (150)

The village elder before his death tells Ozuna, “the most important thing is to find out what your purpose is while you’re here on earth.” (85) And Takeru follows this up with the advice to “lead a finite life as best you can, with no regrets,” (86) his goal being to finish his history (which he does before Ozuna kills him). Ozuna in the end, sacrifices his own life, in the goal to stop the human sacrifices.

In “Dawn” and many of the other stories, the phoenix is a creature hunted by men in search of immortality. Here, Ozuna does not seek immortality. He communicates with the phoenix, plays music for it, in his attempt to save others with some of its blood, not for his own gain. We might contrast this with his father’s foolish attempts at immortality, not through the phoenix but through manmade objects. In the end, despite being buried alive, Ozuna dies happy unlike his father.

One element of the story, and Ozuna’s choices in living his life, that bothers me is that he kills Takeru at all. In killing Takeru, Ozuna claims to respect the man, but says he has to kill him so as not to be a traitor to Yamato. While this event precipitates the plot events that follow (Ozuna fleeing, Kajika chasing him), the killing seems unnecessary from a thematic point of view. Killing Takeru falls into the plans of the king of Yamato, whom Ozuna immediately goes back and plots against anyway (by making his tomb a playground). Killing Takeru does not help the people of Yamato at all, the people who seem to be Ozuna’s real interest (stopping the sacrifices). Ozuna uses the killing as a motivational force, an excuse to get himself to flee Kumaso (where he is tempted to stay by his love for Kajika) and go home where he will continue with his plan to save the sacrifices. In the end, had he not killed Takeru, Ozuna would probably have ended up in the same place anyway. I don’t see the killing as helping the plan to save others, and thus not justified in any sense of living life rightly.

In the comments to my “Future” post, Matthew Brady pointed out some powerful scenes that I neglected to mention. In one, the now immortal Masato shoots himself in the head, then gets up again. In another he spends centuries visiting a capsule that contains a person in some kind of cryogenic state, only to discover in the end that the capsule contains only dust (remains). Both are harrowing images of suffering. Suffering as a thematic element of these stories is worth mentioning. The concept of suffering is a major part of the Buddhist “Four Noble Truths,” which surely is part of Tezuka’s goal. In this story, the ending finds our protagonist and his love interest buried alive for a year. Tezuka does not play it as horror, in fact, it comes off almost humorous to me (they shout sixties style slogans from under the ground), and has a tender love scene between Ozuna and Kajika. Tezuka plays down the suffering here, which he does not do in “Future.” The protrayal of suffering is something to watch for in the other stories and think about how it is portrayed.

I just love the way this page shows a single large tree broken up into panels to show two scenes at different times of day. On the left Kajika and a suitor walk by the tree during the day, while on the right Ozuna and his two soldiers spend the night under the tree. For both characters, shortly after their meeting, they are questioning loyalties. The page nicely places these moments next to each other.

This earlier page also has two trajectories to it, the phoenix above and the characters below, though in this case they exist simultaneously. I love how the page ends with Kajika looking up at the phoenix in the previous panel. Also note the anachronistic literary reference.

Here are the portraits of the king of Yamato I referred to earlier, a wonderful pastiche of art from different places and times.

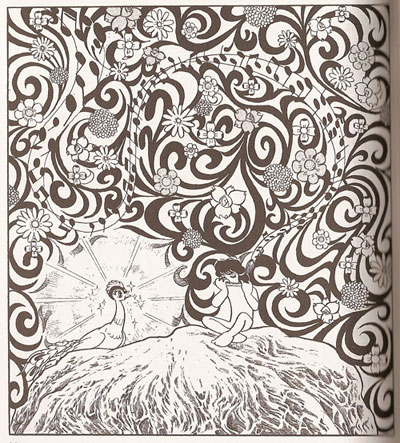

To go with my ongoing sound in comics examples, here’s Ozuna playing his song for the phoenix. The flowery representation looks like something from a shojo comic and is distinctly out of place with the rest of the story’s style. This adds a sense of the power of this music, which attracts the phoenix.

Next: Volume 3 continues with “Space” which features some magnificent layouts.