Bourbon Island 1730 by Apollo and Trondheim

Apollo and Lewis Trondheim. Bourbon Island 1730. First Second, 2008. 288 p., $17.95. ISBN: 9781596432581.

I’ve felt hit or miss with First Second’s releases to this point. But they’ve got two great releases this season, one of them is Alan’s War (which I’ve had since July and haven’t managed to write about yet) and the other is Bourbon Island 1730 by Apollo and Trondheim. Up to this point, the publisher has been publishing Trondheim’s books focused at children, so I was happy to see a different Trondheim being presented with this volume.

Bourbon Island 1730 is a historical fiction set in the time and place of its title. Bourbon Island, now called Reunion, is an island east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. Oddly enough, I’d not heard of Reunion until Trondheim blogged about one of his visit’s there in his online Les Petits Riens strip (I think this sequence is in the first collection of the strips, under the title Little Nothings: The Curse of the Umbrella, from NBM). Perhaps his trip was related to this book, doing on-the-scene sketches for the book (there was a lot of foliage in the sketches, as I recall). I’m also guessing that co-writer Apollo is the historical influence here. I’m not aware of Trondheim doing any previous work in this genre.

The narrative’s protagonist is Raphael, a student ornithologist, who has travelled with his professor to Bourbon Island to search for the Dodo bird, which, rumor has it, was seen on the island. We quickly learn that Raphael is more interested in pirates than birds, attaching a romantic notion of freedom and brotherhood to them.

Concurrent with Raphael’s arrival on the island, a former pirate captain is captured and the struggles of the various island factions are brought forth as a result of the possibility hidden treasure and because of the captain’s symbolic nature as the last pirate captain. The island is home to plantation owners, slaves, freed slaves, runaway slaves (“maroons”), and amnestied pirates all are which are given varying amounts of story time in a rather complicated plot.

The theme of freedom is one of the primary foci of the book, from the former pirates who look back on their days of violent freedom from their current place in the social structure to the maroons who hide in the mountains always wary of capture. Raphael’s romantic notion of freedom obscures the real violence and horror of the pirates’ actions, while Virginia, a plantation owner’s daughter, dreams of running away to freedom with the maroons and holds a romantic notion of a tragic death.

Raphael remains mostly an observer to the larger actions that swirl around the island, yet the primary thread of the book is a kind of bildungsroman. During the progress of the narrative, Raphael loses some of his naivety and gains an education about freedom and the social order. This is satisfyingly shown in the last scene of the story. It’s an engaging story, that requires the reader’s attention. Despite the serious subject matter, the story is lightened with humorous scenes and asides (one would not expect any less from Trondheim).

Bourbon Island 1730, besides having a good story, is a rare example in English of Trondheim working in his pared down black and white style. The drawings are reminiscent of his earliest works like Lapinot et Les Carottes de Patagonie yet shows the progress of years of experience and refined style as seen in Désoeuvré. I enjoy the lushness of the watercolors in Trondheim’s recent autobiographical work (see Little Nothings) but something about the spare line drawings really appeal to me. There is an almost chaotic business to many of these panels, particularly with the abundance of foliage. The line is loose, has only the slightest variation in line weight, and is almost never used for shading, yet I was never confused as to the focus of the panels. Through composition and the use of spot blacks, the panels are always clear even at their most chaotic. The drawings look so casual, yet clearly the ease of these images is deceptive.

Since I’ve been posting about point-of-view recently, I noticed a view examples to share. When we are first introduced to Virginia, the plantation owner’s daughter, it is through an extended p.o.v. sequence. She looks out into the forest. Retrospectively, we know she is dreaming of running away and her freedom. The first panels set up the character at the window, then looking out, after which the rest of the page is clearly showing her gaze. Note the last panel of the first page which appears to show the shadow of a figure in the grass. The second page shows the girl again to reiterate her presence and gaze before she walks out into the night. This is a good example of secondary internal ocularization (see the article linked from “point-of-view” in the first sentence of this paragraph).

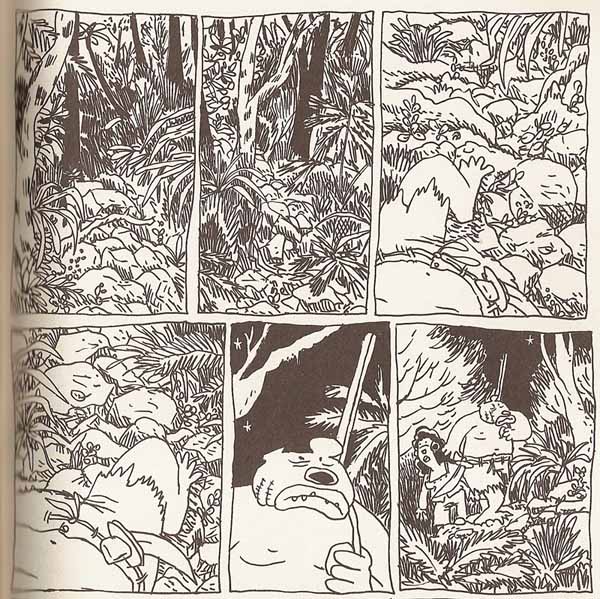

A different type of p.o.v., primary internal ocularization, appears on this page, where we see panels showing a character from his own perspective. The way the lower part of the body juts out from the bottom corner of panels three and four, indicates we are seeing from the character’s gaze. We could also retrospectively assume that panels 1 and 2 are from the character’s p.o.v. He is looking forward towards the trees, then looks down at the ground.

I also noticed a few interested examples of narration. In one sequence across many pages, a story related to the captured pirate caption and his treasure is told by three different narrators. The narrative balloons seems to travel across the island from one narrator to another so that the reader doesn’t know where one narrator stops and another begins, effectively blending the tale into a single shared story. On this page which starts the sequence, the first ex-pirate, whose boots we see in panel one, starts the story on the previous page. The next page has a second ex-pirate telling the story to Raphael. We see their feet in panel six of this page. The sequence continues to other characters and back to the first narrator.

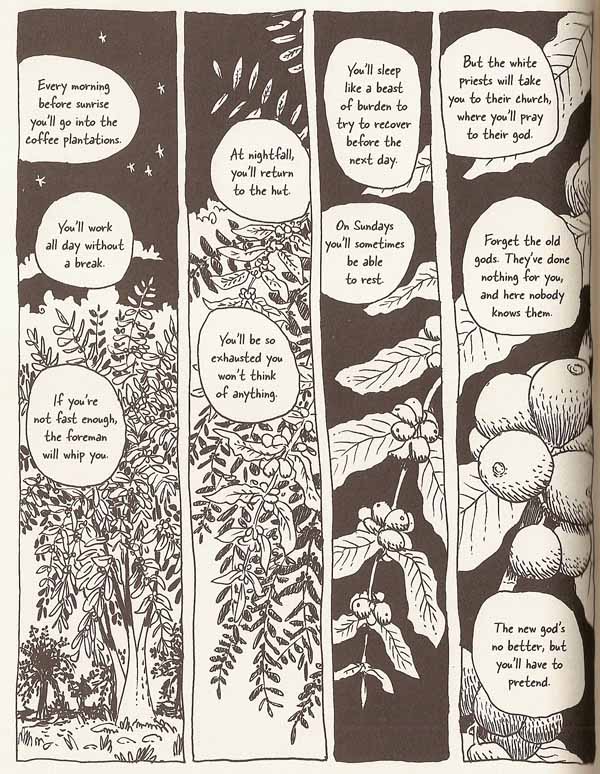

In this other narration example, the same ex-pirate from the previous example is now talking to a newly arrived slave, answering the question “What’s going to happen to me?” As he discusses the life of a plantation slave, the panels slowly zoom in on coffee plants, the major product of the island which is exported back to France. For Raphael, the coffee later becomes a symbol of the lack of freedom of the slaves.

I highly recommend this book as a thoughtful and enjoyable comic. It’s of considerable length and depth without being a brick. A few pages of notes in the back will help out with historical context and facts. I hope we’ll be seeing more of Trondheim’s more grown-up works soon. I’m still waiting to see a completion of the project to translate the Lapinot books, perhaps in collected volumes of multiple stories, instead of the short European album format that Fantagraphics tried some years back.

(You can read a 10 page excerpt at the First Second site.)

P.S. This book has that annoying jagged binding which makes it really hard to page or flip through the page. I hate that. It lowers the usability of the book. None of the other First Second books at hand use that? Is it some kind of misguided attempt at giving the volume a historical feel? If so, bad idea.